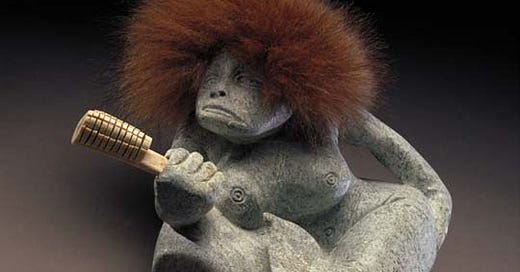

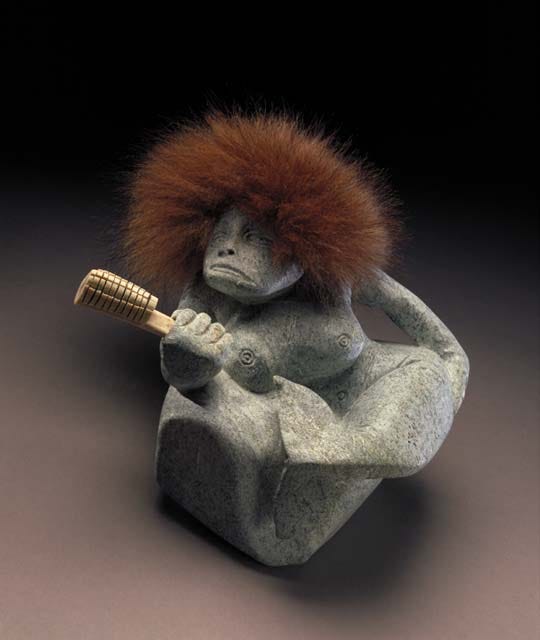

Natar Ungalaaq, Sedna with a Hairbrush, 1985.

Years ago, when I was trying to do a more traditional astrology blog, somebody asked me a question about Sedna. I was…well, aware of Sedna’s existence. That was about it. But I did some research and gave the person an answer. What I really found out, though, is that most of your usual sources on astrology are astonishingly ill-equipped to talk about Inuit mythology. Like, riddled with errors. Borderline unusable.

Time passes. Empires rise and crumble. I can’t stop thinking about Sedna.

So I wrote this, and it’s long. I broke it into three parts for you. There are pictures, lots of them especially in part 2. Perhaps now I may find rest.

Western astrology owes a lot to its Mesopotamian precursors, but its present-day cast of characters consists mostly of Greek and Roman archetypes. Very recently, that has started to change. There are a few sky objects now named after indigenous mythological figures: the trans-Neptunian object Quaoar (Tongva creator deity/culture hero), possible dwarf planets Haumea (Hawaiian goddess of childbirth) and Makemake (Rapa Nui creator of humanity), minor planets Tomaiyowit and Tukmit (Luiseño earth mother/father sky couple), asteroid Atira (Pawnee goddess of earth and the evening star), and two near-earth asteroids named for the Aztec deities Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca. And Sedna.

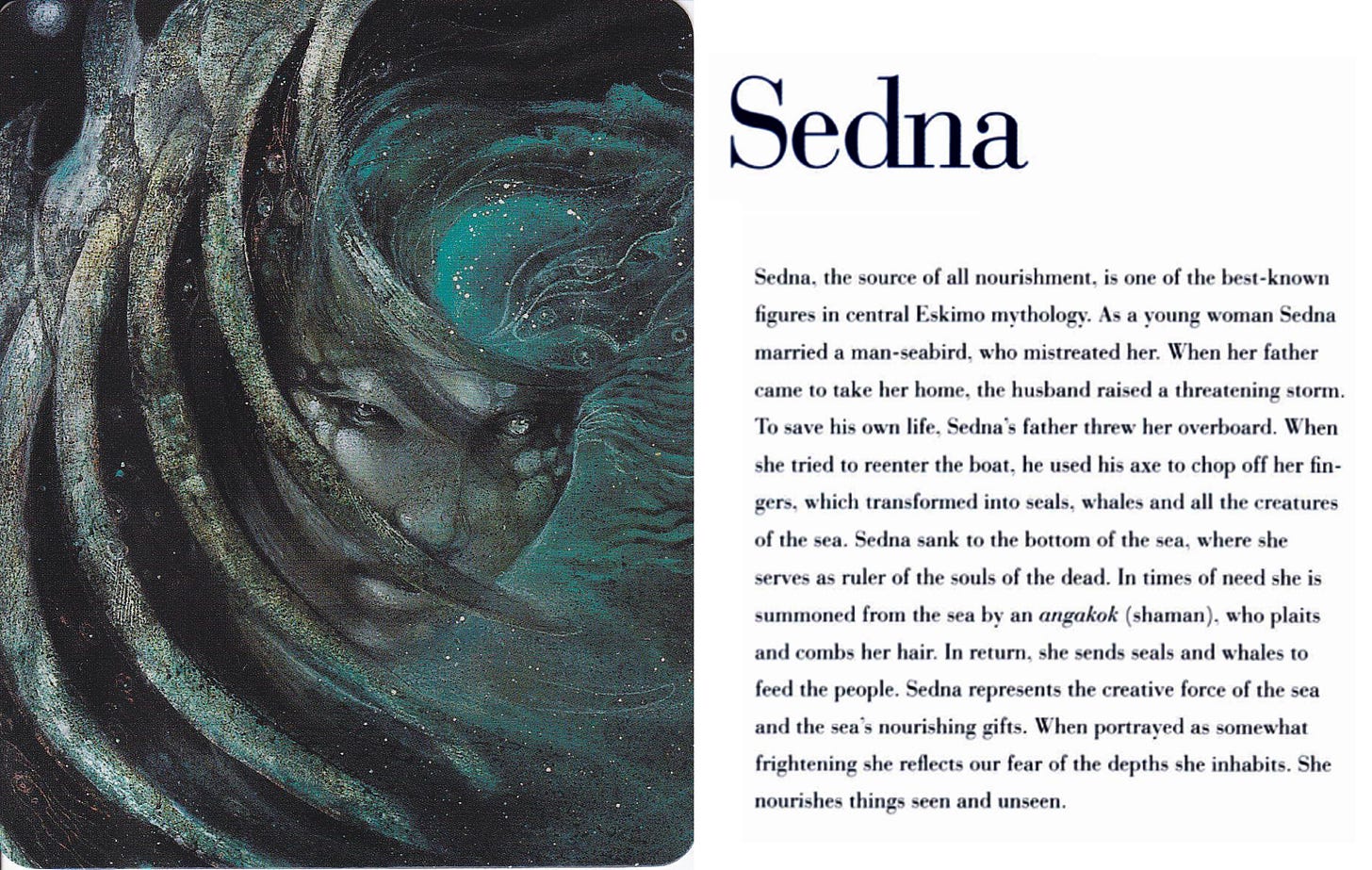

Among astrologers, Sedna is more famous than most of those listed objects, and her story is modestly well-known. Magical folks might have first encountered her via Susan Seddon Boulet’s Goddess paintings and oracle deck:

(from Susan Seddon Boulet: The Goddess Paintings, Susan Seddon Boulet and Michael Babcock)

We’ll be giving this story a closer read later on, but for the moment, that’s a good summary of Sedna’s public image among new age/occult types in the south.

(N.B. “the south” does not mean below the Mason-Dixon line, for our purposes. It means south of North America’s boreal forests. I may as well add the disclaimer here that I’m a southern settler myself, as obvious as it is.)

Sedna’s Discovery

I wish I had a kicky little Schoolhouse Rock summary for how a newly-discovered sky object becomes a part of contemporary astrology. Unfortunately, it’s a slow, boring process that doesn’t lend itself to fun videos. But in some respects, we treat new planets just like we treat new human beings: when we want to find an astrological understanding of something, we look at the circumstances of its birth.

In other words, how did this sky object come to our attention?

Astronomically speaking, Sedna is a (possible) dwarf planet, like Pluto. She has no moons, and her surface composition is largely water, methane, and nitrogen ices. Her orbit is eccentric and incredibly long, taking about 11,400 years to complete.

Her slow movement originally masked her presence from the team of astronomers who discovered her in 2003. One of those astronomers, Michael Brown of Caltech, initially nicknamed her “The Flying Dutchman” (“Dutch” for short) because of that slow, ghostly movement.

But Brown soon gave her a proper name, Sedna. He’d previously named other sky objects after indigenous mythology—he also discovered Makemake and Haumea—and he chose Sedna’s name because he thought a cold, distant planet should have a name from a polar culture.

“Our newly discovered object is the coldest, most distant place known in the Solar System, so we feel it is appropriate to name it in honor of Sedna, the Inuit goddess of the sea, who is thought to live at the bottom of the frigid Arctic Ocean. … We will furthermore suggest to the IAU that newly discovered objects in this inner Oort cloud all be named after entities in arctic mythologies.” (Brown)

That source link goes to Brown’s endearingly Web 1.0 personal website at Caltech. He follows this explanation with five links to Sedna’s story. Fantastic! Let’s see which versions of the story he was aware of when he made this decision!

(Because there are a lot of versions.)

The first three are 404s. Darn.

The fourth link goes to a version written for children by Lenore Lindeman, a combination of several stories. The fifth link is (I’m not kidding) just a link to a google search for “Sedna.”

Okay, well, 404s happen on webpages this old. We won’t hold this against Michael Brown, but we don’t have much evidence here that he knew a whole lot about Sedna’s mythology at the time.

(Similarly, he chose to name the other object Makemake because it was discovered around Easter, and Rapa Nui is better known in English as Easter Island.)

Other Sednas

“My favourite work is on Taleelayu—women figures.”

— Sculptor Oviloo Tunnillie, 1992

Let’s take apart that story we heard earlier from the Babcock/Seddon Boulet book. The first problem we stumble over is that Seddon Boulet painted “goddesses”, a term that doesn’t necessarily work very well to describe Inuit cosmology. Rachel Qitsualiq-Tinsley writes that Sedna is, in fact, “not a goddess, but rather a special creature of fear and tragedy.” (The Problem with Sedna)

Another problem is that Sedna itself is a name attached to her by the anthropologist Franz Boas, an anglicised form of “Sanna”, which means “down there” in Inuktitut. Many European cultures had similar traditions of using euphemisms for feared deities, such as the Romans’ vague term di inferi (“gods below”) for the gods of the underworld.

Her other names in various communities include Nuliajuk, “the evercopulating one”, Taleelayu or Taleelayo (this name is usually just glossed as “Sedna”, frustratingly), and Takánâluk Arnâluk or Takannaaluk, “the [horrible] one down there.” When her character is first introduced at the beginning of the story as a mortal woman, her name is Uinigumasuittuq (“she doesn’t ever want to take a husband”).

The beginning of Sedna’s story varies the most, while most of the variants come together on the ending. In most versions she has a father (and sometimes brothers), although the Netsilik Nuliajuq is sometimes said to have been an orphan who was mistreated by her community.

“In many versions of the story, she is initially married to a dog husband, and her children become the first members of various non-Inuit groups, especially the allait or itqiliit (Indians) and the qallunaat (white people). In the eastern Canadian Arctic and Greenland, the young woman’s second marriage to a bird-husband generally results in the creation of the sea-mammals, and in the young woman’s transformation into the sea spirit.” (Keavy Martin, Rescuing Sedna: Doorslamming, Fingerslicing, and the Moral of the Story)

Martin’s article, which is great, goes into considerable detail about how the versions of this story have been censored and bowdlerised for Southern readers, under the presumption that settlers would be too shocked by the mutilation of Sedna’s hands. I think that’s true in many contexts (especially children’s storybooks), but I also notice the opposite trend in art by non-Inuit folks, which I’ll get to in the next installment.

Many of these “less bloody” versions of the story take it easy on the father, saying that he “panicked” and that Sedna’s fingers broke apart after freezing in the water. This version from the Eastern Arctic emphasises that before Sedna, there was literally nothing to hunt and people existed in a state of permanent starvation. Easier to cut the characters some slack for making harsh decisions if the situation was that bad, right?

These are Inuit writers who are (usually) censoring themselves, rather than being actively censored by settlers. They don’t want to contribute to the racist stereotype that Inuit culture is violent, primitive, or cruel. But these edits to the story can also contribute to the equally colonialist image of indigenous mythology as Pure and Noble, so it’s a no-win situation.

Martin again:

“In the tale of Sedna, the violence leading to the wife’s transformation is crucial to the sense of the story. The sea-woman’s ability to withhold the animals means starvation and a slow death for the people; this devastating power, and this monumental ill-temper, are a direct consequence of horrific actions of the father (and perhaps also of the bird-husband). The story thus posits an explanation for the brutality of famine, and reminds the inhabitants of a highly-interconnected cultural landscape of the wide-reaching consequences of their actions. The danger, however, is that these subtleties may be lost on contemporary readers, who may mistake the story as condoning violence against women.”

We wouldn’t interpret the story of Oedipus, for instance, by assuming that Greeks believed it was okay or normal to marry your mother and kill your father—or, for that matter, to claw out your eyes or meet sphinxes. Inuit culture treasures children and places very high value on family bonds. However we interpret the story of Sedna, we shouldn’t leap to the conclusion that this violence was baked into traditional Inuit culture.

It may, however, reflect the fears of young women preparing for marriage, and the traumas recalled by elder women. European folklore likewise has plenty of stories in which a young woman is married off to an animal or a monster. Sometimes the bride learns to remove the enchantment on her husband, revealing a normal human man underneath; sometimes she can only flee.

Sedna has to flee. Her father comes for her, and she almost has a chance to get away, but her bird-husband summons a storm. Her father reacts. Is it panic? Is it ruthlessness? Did he never really care about her at all, or does this act represent the crumbling of a man’s best self under enormous pressure, something he’ll regret for the rest of his life?

We don’t know. We only know what he did to Sedna. And now you know it too.

You know that she feels hurt and betrayed, abandoned, her agency taken away from her when she prized her independence so highly. She only has her children to keep her company, and hunters keep taking those away. Some of them don’t even show her any gratitude. She’s not a cruel person, but she wants respect. She wants to be heard, understood, taken care of.

Now that you know her story, can you better understand why the sea is the way she is?

Coming up in the next post, we look at some examples of Sedna in art.